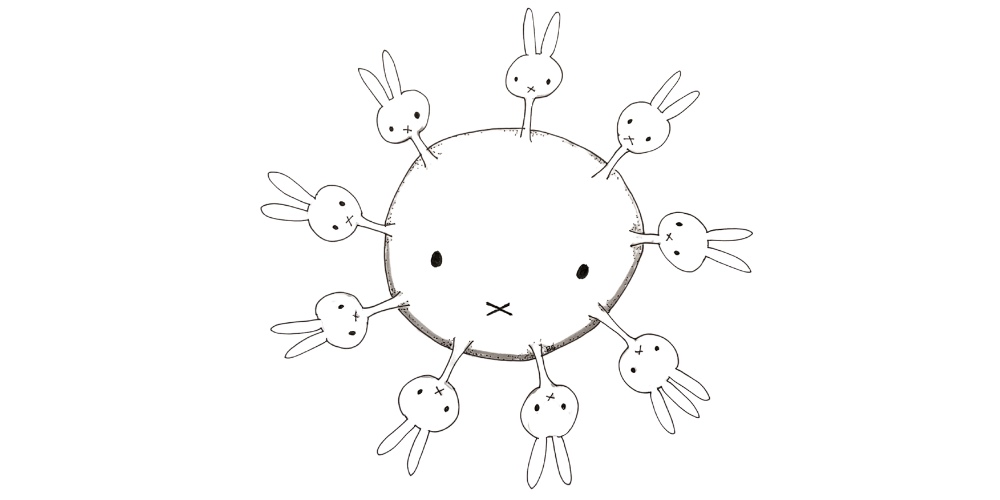

The Year of the Coronabbit

Published on 30 January 2023 | By Ren Ee Chee and Benjamin Seet | Source: The Straits Time © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

Illustration:

Benjamin Seet

Illustration:

Benjamin Seet

We have entered the fourth year of the pandemic. Billions have likely been infected and the official death toll exceeds six million. More than two-thirds of the world’s population have received at least one dose of Covid-19 vaccine, with 92 per cent of people in Singapore having completed their primary vaccination series.

The Covid-19 virus has gone through a number of iterations, but there are no signs that it will go away. Notwithstanding, borders and communities have reopened, with anticipation of life returning to normality. The question on everyone’s mind is whether we have truly defeated Covid-19. Is the worst over? Or will the virus make a comeback that will give us little choice but to retreat to the measures of recent years?

What will the virus do next?

Quoting Sun Tzu’s Art Of War, “Know the enemy and know yourself, in a hundred battles you will never be in peril”, there is still much that we do not know about the Covid-19 virus. As its genetic evolution continues to take a random and uncharted path, it is a challenge to predict with certainty what this enemy will do next. But we have accumulated considerable knowledge about the tactics it employs to invade our cells, and we are better at tracking these changes.

Through 2020 to 2022, starting with the ancestral strain from Wuhan to the current Omicron, we have witnessed the virus’ propensity to infect cells. It does so by modifying its spike protein to enhance the ability to breach and enter cells. At the same time, these spike mutations have helped the virus evade the body’s immune defences, by reducing the effectiveness of protective antibodies created by previous infections and from vaccination.

The current soup of Omicron variants reveals that Covid-19 is still a formidable adversary. Nonetheless, at the population level, the havoc that the virus currently wreaks on those infected has become milder. This may be attributed in part to the protective efficacy of vaccines, but does not mean that the virus has adapted to the human host. Its sole mission has always been to propagate its genetic material and to ensure its survival as a species. Victory is achieved once it infects a new person, and within a week or so, when it spreads to more people. What subsequently happens to the infected hosts is merely collateral damage. This can be dangerous, and even lethal, to frail, vulnerable and unvaccinated individuals.

While it is hard to predict or model with precision what the virus will do next, its natural course would have been altered by vaccines and other measures that countries have adopted to protect their citizens. The world is now made up of people vaccinated and boosted with varying doses of different vaccines, with many having hybrid immunity following infection with one or more Covid-19 variants or sub-variants.

The best-case scenario is for the virus to keep shuffling its mutations and to remain a close kin of Omicron. In this setting, Covid-19 becomes endemic and part of the infectious disease landscape we will have to coexist with. The worst case is for it to exchange genetic material with another virus, producing a more sinister offspring that may not be entirely coronavirus in nature and behaviour. This is the Virus X scenario that the world needs to prepare for.

How can we continue to Protect ourselves?

Even as the Covid-19 virus evolves, it is highly unlikely that it would become capable of completely avoiding detection by our immune system, which remains sufficiently powerful and sophisticated to deal with infection in most people.

Our understanding of the virus’ genetic sequence has further facilitated the development of drugs and vaccines against its Achilles heel, the spike protein.

When vaccines first became available, the original idea was to achieve herd immunity, where enough people were protected to prevent further spread of infection in the community.

When it became apparent that this was not achievable, the focus shifted to protecting the vulnerable, as well as reducing the risk of serious infection and the need for hospitalisation.

While these goals were largely achieved in many countries, expectations to fully rid ourselves of the virus continue to be thwarted.

Protective antibodies produced following vaccination or infection tend to wane over time.

These also became less effective as new variants and sub-variants emerged, and, coupled with spike mutations that improved infectivity, it meant that the virus continued to have the upper-hand.

This led to vaccine breakthroughs, as well as multiple rounds of Covid-19 reinfection in some individuals.

The entire arsenal of monoclonal antibody drugs was also rendered less effective against the latest variants.

In response, we found that boosters helped to strengthen our immunity against the virus. Global efforts to track genetic variations of the spike protein also meant that we could observe its evolution in real-time. This has led to the development of updated bivalent vaccines that are closer matched, offering better protection against the prevailing viral strains.

For now, the best course of action is to take advantage of the current lull to keep up to date with Covid-19 vaccinations… In this year of the “Coronabbit”, we can be optimistic that in the war between humankind and virus, the outcome will be steadfastly in humankind’s favour.

We have so far been one step behind in this global war between man and virus.

Looking ahead, doctors and scientists are deliberating on the need for annual boosters, in the same way that we have protected ourselves against the constantly evolving influenza virus.

The current bivalent vaccines are now our main line of defence. While vaccine companies may not go “variant-chasing” to catch the latest wave, they will do so when differences between the current and emergent Covid-19 viral strains substantially degrade the efficacy of vaccines.

There are also efforts to create a universal vaccine that is variant-proof, although the technical challenges could make this elusive for some time.

For now, the best course of action is to take advantage of the current lull to keep up to date with Covid-19 vaccinations.

This would better prepare our body’s defences against what comes next.

In this year of the “Coronabbit”, we can be optimistic that in the war between humankind and virus, the outcome will be steadfastly in humankind’s favour.

Professor Ren Ee Chee is an immunologist and principal investigator at A*Star’s Singapore Immunology Network, and adjunct associate professor at the NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine. Professor Benjamin Seet is deputy group CEO for education and research at the National Healthcare Group. Both are members of the Therapeutics and Vaccines Advisory Panel and the Expert Committee on Covid-19 Vaccination.

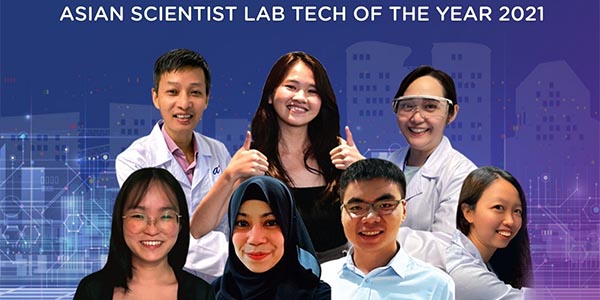

A*STAR celebrates International Women's Day

From groundbreaking discoveries to cutting-edge research, our researchers are empowering the next generation of female science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) leaders.

Get inspired by our #WomeninSTEM