A*STAR NEWS

PUBLICITY HIGHLIGHTS

Using AI to interpret eye images for major health risks

It can screen for life-threatening conditions like brain tumours

Published on 4 July 2020 | By Joyce Teo | Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

An artificial intelligence (AI) system can look at photographs of the back of the eye and accurately detect if there is an eye condition that points to a brain tumour or other life- or vision-threatening conditions.

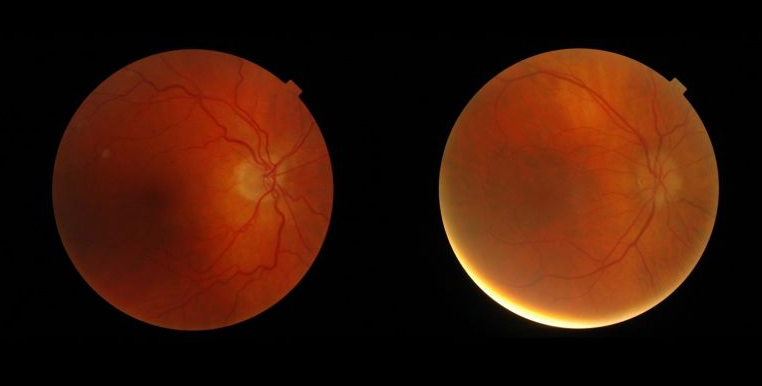

Images of the ocular fundus (inside, back surface of the eye) showing the optic nerve head - the region where the blood vessels converge - in a normal patient (left) and in a patient with subtle abnormalities associated with a brain tumour.

PHOTOS: SINGAPORE NATIONAL EYE CENTRE

It sounds almost too good to be true, but Professor Dan Milea, a neuro-ophthalmologist and a senior consultant at the Singapore National Eye Centre (SNEC), said this game-changing concept has recently been proven.

AI has recently been used to detect various ophthalmic diseases, such as diabetic retinopathy.

SNEC’s deep-learning AI software system Selena+, which can detect whether someone has diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma or age-related macular degeneration from a photo of that person’s eye, was approved for use in Singapore only last October.

Now, AI has been shown to be able to make inferences about rare but serious conditions, not in the eye, but in the brain, by interpreting photographs.

A global study has shown that an AI system can look at images of the back of your eye and rapidly identify various optic abnormalities.

Importantly, it can accurately detect a specific type of optic nerve abnormality known as papilledema, which is linked to life- or vision- threatening diseases of the brain, such as brain tumours.

Papilledema is the swelling of the optic disc (or optic nerve head) due to pressure build-up in or around the brain.

The AI system has a 96 per cent sensitivity, meaning that it can pick up 96 out of 100 images with papilledema, said Prof Milea, who is also head of the visual neuroscience group at the Singapore Eye Research Institute (Seri).

While rare, papilledema can lead to blindness or even death, he said.

"Thus, the appropriate identification (of papilledema) on a simple photograph can alert doctors who do not have expertise in ophthalmology to the possibility of a severe brain condition that may otherwise get overlooked," he said.

"If further validated, this method may improve detection of brain and optic nerve abnormalities in patients who do not have other obvious signs of the disease."

The study, Artificial Intelligence To Detect Papilledema From Ocular Fundus Photographs, was published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine in April.

A journal editorial on the study had concluded that "the breadth of this study makes it likely that some versions of these automated systems will make their way through regulatory approval and into the clinic".

The AI system was developed in Singapore by a collaborative group including researchers from Seri, Duke-NUS Medical School and the Agency for Science, Technology and Research.

Prof Milea said the system would be particularly helpful in emergency departments, in neurology practices and even in general practitioner clinics.

He offered the following scenario: Someone walks into the emergency room at 2am, complaining of a very bad headache but otherwise having no symptoms of visual impairment, such as blurred vision.

The patient would not get to see an ophthalmologist at that time, and may instead be sent for brain scans to rule out the small chance of a stroke or bleeding in the brain.

The AI system would be able to give an answer in a few seconds at minimal cost, he said.

"Detecting this, I can say: This guy goes to the top of the queue for a scan. This guy has high brain pressure. There is bleeding or something growing in the brain and that can cause death."

Professor Wong Tien Yin, SNEC’s medical director and one of the study’s authors, said the power of AI in this area is unmistakable.

"At the ED (emergency department), sometimes the doctors should look at the optic nerve but don’t for lack of experience and expertise," he said.

However, if there is swelling of the optic disc, you would be prioritised for a scan, he said.

Prof Milea said it is just as important to rule things out. "If there’s nothing wrong with the eye, the doctor can confidently send the patient back home," he said.

That is a big deal, as expensive, unnecessary and sometimes dangerous investigations like a lumbar puncture can be avoided.

The study involved more than 7,000 patients from 25 centres around the world, and the AI system was fed with 15,846 ocular fundus photographs from individuals of multiple ethnicities.

It was a major undertaking to collect so many images and Prof Milea, who is originally from France and has worked in other countries, said he tapped his contacts to do so over a period of about two years.

"Papilledema is rare... In this study, the machine was trained by being exposed to more pictures of papilledema and other optic disc abnormalities than what one specialist can see in a normal practice over a long career," he said.

"Transferring such skills to AI-based medical devices may contribute to evolving new ways of practising medicine at a distance, in order to better protect patients and healthcare providers, especially in our Covid-19 era," added Prof Milea.

"We are currently conducting a pilot prospective, real-life study at SNEC. The next step is to extend this pilot by including other international centres for another large international study in the very near future."

Was this article helpful?

A*STAR celebrates International Women's Day

From groundbreaking discoveries to cutting-edge research, our researchers are empowering the next generation of female science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) leaders.

Get inspired by our #WomeninSTEM